Modern User Sessions

Stateless Session Craze

“Stateless session” concept using JWTs is all the craze these days and there are a lot of misleading articles and books on this topic that focus on its benefits without mentioning any of its drawbacks. The goal of this post is to offer an unbiased opinion the subject.

Absence of Session State on the Backend

The use of JWTs is not as simple as it seems on the surface. One of the claims of the JWT standard is that since its tokens are cryptographically protected(cannot be altered since issued by the server) and carries an expiration time(exp), there is no need to maintain any state on the backend. Unfortunately, this is not accurate. Regular session IDs can also be cryptographically safe if signed with an algorithm such as HMAC-SHA256. Furthermore, being cryptographically safe does not mean we can get away with not maintaining the state on the backend. In OAuth 2.0, a session consists of two tokens: a short-lived access token to make API calls and a long-lived refresh token to generate new access tokens. Given this, if the architecture chooses not to maintain any session state on the backend, it gives up session invalidation. It renders the following features utterly meaningless and broken: password reset, account enable/disable, logout, and invalidation of the current active session when signing in with credentials. A given user can access protected APIs by generating infinite amount of access tokens as long as the refresh token’s expiration time is still in the future. In a way, exposure of a refresh token to the client without a revocation list is worse than storing credentials on the client-side. With stolen credentials, the attacker still has to bypass MFA. With a stolen refresh token, there is nothing to bypass. This phenomenon increases the risk of replay attacks and creates a system that cannot even control how its users access it. The theft of JWTs is an extremely nightmarish situation if no state is maintained on the backend. While using JWTs, the expectation is to return a refresh token with an expiration date is not in the near future. While this is well and good if you are building an internal app or a mobile app that can enforce a revocation list based on a unique mobile device ID. However, this is not a feasible compromise in a consumer-facing serious web application. For instance, a user could log in and shut down their laptop. They can come back a few hours later and continue to still reach the protected APIs by using their refresh token to generate access tokens. A user could click “logout” and due to a network failure, the API call may not occur. According to the system, unlike in a stateful system, their session is still alive until the expiration of the refresh token. On top of that, if we are not maintaining any session state in a DB, a user’s account can have numerous simultaneous active sessions, because, as per some providers such as AWS Cognito, there is no functionality to limit the number of simultaneous active sessions.

However, once you maintain a revocation list, all the touted benefits of JWTs start to crumble. At that point, one is better off just exposing a good old HMAC-256-signed random session token ID instead of three session IDs(Access token, Refresh Token, and ID Token). To avoid the issues associated with the powerful refresh token, one would think that one can sidestep them by getting a new refresh token as we get a new access token. However, unlike Auth0 and Okta, Cognito does not support refresh token rotation, thus not offering a way to reduce refresh token’s powers and make for a safe and seamless user session experience by keeping the session alive only as the user continues their activities on the site. Refresh token rotation is also recommended to service providers by the IETF OAuth spec. Unfortunately, while using Cognito, one cannot get a refresh token without providing user credentials. This limitation is unreasonable as it makes session extension impossible while keeping a short-lived, say, 30-minute refresh token. At the end of 30 minutes, the user will be logged out from the site and forced to re-login. On top of this, Cognito does not maintain a programmatically queryable revocation list, nor does it expose the IDs of refresh tokens issued to a user. It only provides an API to revoke a refresh token. The application itself has to maintain all the state to keep track of refresh tokens. Once a refresh token is revoked explicitly via the AWS API, the previously generated access tokens are only invalidated in the sense that they can no longer be used to access Cognito user pools. None of the backend systems know the fact that the access token was revoked because the token does not cary that information. Cognito does not have an API to check if the access token was revoked. You only find out about it the moment you try to access a Cognito user pool with it and there’s a failure in the API call. So, even though AWS is maintaining a state, your systems would not be aware of that state. If on each request to a protected API we are supposed to make an artificial call to Cognito to find out if the access token was revoked, we would be misusing JWTs. They are supposed to encapsulate the state within themselves and obviate the need for look-ups on the backend. This also has bad performance implications; the artificial HTTP call to Cognito user pool to check if the access token is alive is more expensive than the 1ms lookup call to Redis. Whereas if you maintain state in a DB, you only need to interact with Cognito every 15 minutes to extend the session (by grabbing a new access token).

To reign in the refresh token’s power, one could also think about introducing an custom-generated random session ID, without which the presence of all OAuth tokens would be deemed useless. But this complexity is unhealthy, error-prone, and difficult to maintain; the system would be dealing with four session IDs. Aside from increasing the number of places where things can go wrong, we would also be increasing the bandwidth usage as tokens need to be sent over the wire on each request.

In addition, JWTs do not prevent CSRF attacks; the claim is that by storing tokens in localStorage, CSRF attacks are made impossible. The issue is that when session tokens are not stored in cookies with the HttpOnly flag turned on, you open up your web application to all kinds of XSS attacks. Preventing CSRF attacks today is as easy as setting the SameSite cookie attribute to “Strict” and using application/JSON in API payloads. Cookies have a 4kb storage limitation, which is why the JWT community recommends storing tokens in localStorage due to their payload size.

On top of that, using frameworks such as Amplify in most cases is misguided. They are not only unsound from a security point of view, but are also poor from a system architecture point of view because they directly couple the UI to Cognito and create a “leaky” abstraction. Instead, the UI should deal with the custom abstraction layer provided by the API gateway. The authentication concern should be dealt with at the gateway level so that the downstream services can apply the single responsibility principle and focus on their service duties without having to bother with authentication except for checking the validity of the token handed to them (without doing I/O).

Here are some sources that talk about the issues mentioned above in detail:

Stop using JWT for sessions - joepie91’s Ramblings

Stop using JWT for sessions, part 2: Why your solution doesn’t work

JSON Web Tokens (JWT) are Dangerous for User Sessions—Here’s a Solution

JWT should not be your default for sessions

Please Stop Using Local Storage

Regular Cookie-Based User Session Plus JWT

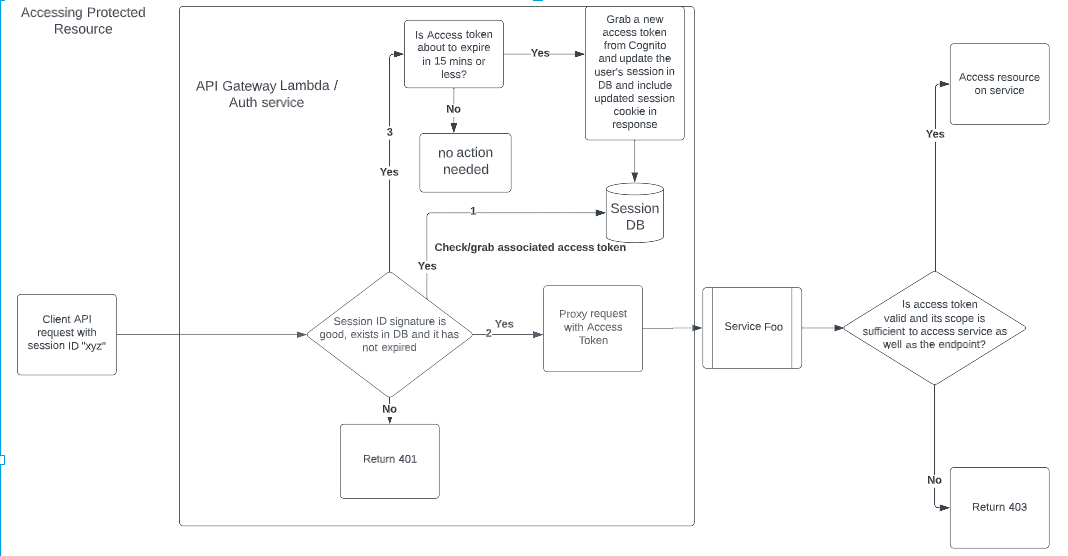

Since the complexities associated with the exposure of JWTs to the frontend

come with serious cons and offer no security benefits over the standard HMAC-SHA256-signed random IDs,

organizations should be relying on traditional session ID-based sessions that involve a look up in a

fast storage. Having said that, JWTs still have a place in microservice architectures,

but their use needs to be confined to the backend. Organizations still want be able to use features of

Cognito such as OAuth 2, account management, user authentication, MFA, and so on.

However, access token and refresh token by themselves are not sufficient to protect backend systems;

they are essentially about accessing the Cognito user pool, thus they cannot be used

in isolation to protect access to backend systems. This is where the regular session_id comes

into the picture to bridge the security gap; if there’s no generated session_id, not only can

you not access the backend systems, but you are also prevented from accessing a Cognito

user pool. Once a user authenticates with a Cognito user pool via the API gateway, the system gets back

the tokens and stores them in its session DB. In subsequent requests, the API gateway should grab

the current access token associated with that session from the session DB and forward the request

to upstream services. As part of the zero-trust architecture, the backend services should not allow

access to a protected API unless a valid access token is present in the request. Thus, by issuing

time-limited access tokens, a service such as Cognito will serve as a ticketing system.

Moreover, using scopes

Cognito can help us determine whether a user can access an API based on

their write and read privileges. It can help us decide what kind of users can access which services.

Since the JWTs are confined to the backend, we are no longer constrained to have short-lived

refresh tokens. Refresh tokens could expire hours later and the access token’s duration could

be equal to the default session duration. This way, we would not have to worry about obtaining a

new access token frequently while making API requests, thereby avoiding frequent latency spikes in

API requests. We can generate a new access token in parallel while handling an API request.

For instance, assuming the session duration is set to 30 minutes, when a request comes in,

we can check the remaining time on the session after validating the session_id and verifying its

existence in a DB. If there is less than 15 minutes left in the session, we can fire an additional

request to Cognito to get a new access token to extend the session’s duration. We can update the

associated session in DB and return as part of the API response the same session cookie with an

updated expiration time. An additional benefit of having this whole abstraction is that in the future

one can build more intelligence into the system down the line. Something like OWASP AppSensor

can be used to harden the security further.

Session ID plus JWT Architecture

Session ID plus JWT Architecture